What is Rose Rosette Disease?

Have you ever seen a rose looking a little bit…weird? It could have rose rosette disease. Here’s our FAQ on the problem, what to do if you get it, and how you can prevent it.

Photos courtesy of:

Jennifer Olson, Oklahoma State University, Bugwood.org

What is rose rosette disease?

Rose rosette disease is a condition that causes roses to grow strangely deformed stems, leaves, and flowers. The disease itself is a virus, but it requires a very tiny mite called an eriophyid mite to transfer the disease between plants. Eriophyid mites are so small that they can only be seen under strong magnification.

How does rose rosette disease spread?

The virus “host” – the plant where the virus originates – is most often multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), a weedy, invasive rose. The disease spreads when the mites feed on an infected rose and are then transferred to another rose by wind, on a person, tool, or animal, or, if the roses are close to one another, simply by walking from one plant to another. The mites settle in to feed on the rose and transmit the virus into the vascular system of the plant. The mites do not fly, but are so tiny that they are readily carried on the wind.

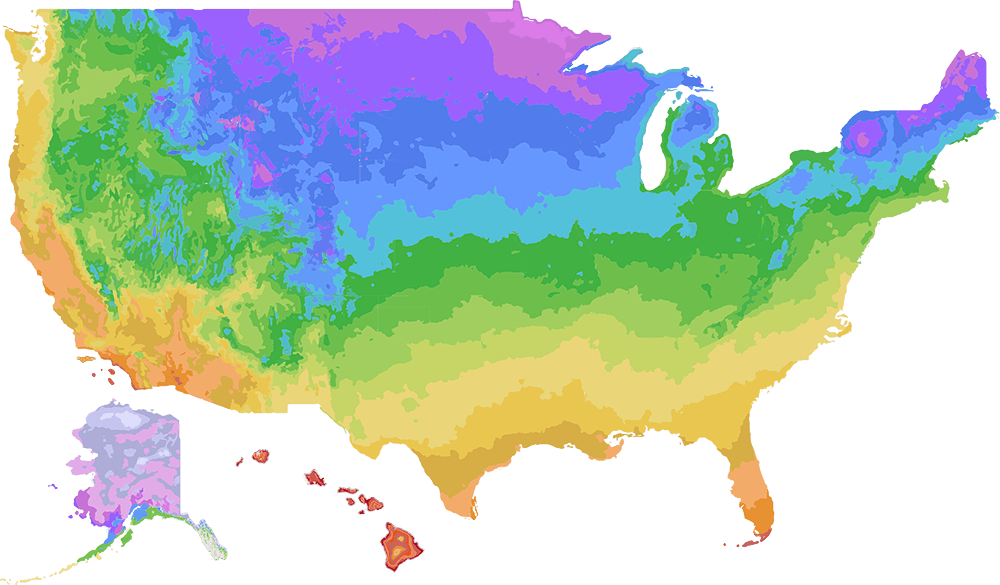

Where is rose rosette disease a problem?

The disease was first reported in 1941 in California, Wyoming, and Manitoba. Since then, it has marched eastward and southward. The highest incidence currently is in the upper South and the Mid-Atlantic, but it appears in the Midwest and Northeast too. Ultimately, any area where multiflora rose grows could host infestations of rose rosette disease. All but nine states and three provinces report infestations of multiflora rose, so the disease potential is very widespread. More infomation from the USDA

What does an infected plant look like?

What does an infected plant look like?

There are several symptoms that a rose infected with RRD may exhibit:

- Bright red new growth that never turns green

- Very thick stems with excessive thorniness

- Flower buds emerge in tiny, tight clusters

(these are the “rosettes” that gave the disease its name; they are also called “witches brooms.”) - Flowers that open are deformed and stunted looking

- Foliage is contorted and stunted looking; may also be yellow

A rose that is infected with the disease may have only one of these symptoms, or it may have any or all of them. The symptoms may be confined to just a few shoots or part of the plant, especially at first. Symptoms may appear any time that the rose is in active growth, but are most likely to be seen in the early to middle part of rose season.

What should I do if I see these symptoms on my plant?

First, report it. Much research is still being done on rose rosette disease, and the universities working on it want your help in understanding its spread. If you see any of these symptoms on roses in your landscape, use this link to upload photos of the affected growth and other details about your plant. They will confirm for you if what you are seeing is actually rose rosette or not.

If reporting confirms the presence of RRD, remove the rose. Unfortunately, simply pruning out the infected portions has not proven an effective control method, and leaving the rose in place just increases the risk of transmitting the disease to other roses in your community. Remove the plant entirely, including the roots. You may wish to cover the plant with a heavy plastic garbage bag to prevent mites from dropping off the plant during the removal. Be sure to close the bag and dispose of it in the garbage – do not compost it or add it to a brush pile.

to prevent mites from dropping off the plant during the removal. Be sure to close the bag and dispose of it in the garbage – do not compost it or add it to a brush pile.

There are some pesticides that have proven to be effective in controlling the mites, but these are not recommended for home use.

Can I replant the area with roses?

It is not recommended – at least not right away. Researchers have discovered that the virus does not survive in the soil, which is great news. But any roots remaining in the soil could still contain the virus, so it’s best to allow a few seasons for those to die completely. It’s also possible that mites that were on the infected plant spread to a nearby rose, which means the disease will be cropping up on those plants in the next season or so.

Instead of planting another rose, we recommend that you replace it with Sonic Bloom weigela. These plants thrive in the same sunny conditions as roses and provide a similarly colorful, long-lasting, easy-care display through summer.

Are there any roses that don’t get RRD?

Currently, there are no roses that are known to be 100% resistant to rose rosette disease, including those that are resistant to other rose diseases like powdery mildew and black spot. Much research is being done on finding roses that are resistant, and while the outlook is good, it will be several seasons still until researchers can definitively say they’ve discovered anything that is truly resistant to RRD.

Is there anything I can do to prevent getting rose rosette disease?

Is there anything I can do to prevent getting rose rosette disease?

Yes! There are several things you can do:

- Prune your roses in late winter or early spring. The mites overwinter in any flower buds or seed heads on the plant, so pruning these off your roses in early spring and disposing of them can eliminate any mites that were lurking on your plant.

- Do not use leaf blowers around your roses. The tiny mites are readily blown by gusts of wind, so this can spread them through your landscape.

- Protect roses from prevailing winds with walls or other plants. Because the mites are blown on the wind, shielding roses from the primary wind direction can minimize the risk of RRD.

- Give your roses plenty of space. Plant them so that the leaves of one do not touch the other, as this makes it easier for the mites to walk from plant to plant. It also helps minimize other diseases by ensuring good air circulation, and healthy, vigorously growing roses are always a good thing.

- Control multiflora rose in your area. Invasive multiflora roses are a big part of the rose rosette equation and their spread is partly responsible for the surge in RRD infections. Learn how to identify multiflora rose and look for it in natural areas near your home. It may grow in parks, woods, fields, roadsides, and farmlands and is most recognizable in early summer, when it is in bloom with small white (sometimes pink) flowers. The small red fruits that follow the blooms are also distinctive – removing the plants at this stage will also help minimize its spread. When you find multiflora rose, remove it by digging it up and either discarding it or leaving it in a sunny, dry spot with its roots exposed to dry up. Get involved with invasive plant clean-up days through your local parks or natural resources department, or organize your neighbors or gardening group to spend a few hours hunting it down and removing it. Removing multiflora roses not only minimizes the risk of RRD, it also helps the environment!

- If you have been around multiflora rose or have removed an infected rose, wash your hands, gloves, and clothes before working in the garden. All could have picked up mites. While the virus that causes RRD does not live very long outside of the plant, mites can be present on your shovel or pruners, so wash these off and wipe down with a household disinfectant before working in the garden again. This may seem like overkill, but the mites are so tiny that they can easily hitch a ride on you or your tools.

Keep up with all of the latest developments on RRD by joining their Facebook page.